THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING?

Constantine Phaulkon - From Cabin Boy to King’s Favourite

Very few people today have ever heard of Constantine Phaulkon, but in the 17th century he became, for a short time, the most influential man in Siam (Thailand after 1939) – not bad for someone who started life as the son of an impoverished innkeeper.

Constantine Phaulkon, the name by which he is known to history, was born Κωσταντής Γεράκης or Costantinino Gerachi in its Italianized form, in 1647 on the island of Cephalonia, which at the time was under the control of the Venetian Republic. His Greek father and Venetian mother ran a small inn, the income from which allowed the family to stay just out of poverty’s reach. At eleven years of age the young Constantine decided that the island offered precious few chances for a better life and so he resolved to run away from home, which he did by joining an English merchant ship as a cabin boy and sailing away on her to London, never to return.

By 1688 he was dead. His vaulting ambition and exceptional talents had taken him to the very pinnacle of power a foreigner could achieve in Siam, but the world he built for himself came crashing down, brought on by events beyond his control. Stripped of his power and considerable riches, tortured and executed, he met his end stoically with great dignity and an acceptance of the vagaries of fate that men who play a bold hand must accept.

Little is known about his life in London or how he survived at such a young age in a dangerous and unfamiliar city, but it seems that he found employment on various merchant ships and, born with an exceptional talent for languages, learned to speak English and Portuguese, the lingua franca of commerce in the East at the time.

In 1669 he sailed on the Hopewell as an assistant gunner in order to obtain free passage to the Indies. On board he met and befriended George White, who was later to play a significant part in the young Phaulkon’s career. White left the ship at Madras (modern Chennai) while Phaulkon continued on to Banten in Java, where he found employment with the East India Company’s factory there.

Here he served in various capacities on Company ships until he eventually became a junior clerk. By this time he had added Malay to his repertoire of languages and through his diligence and hard work had come to the attention of Richard Burnaby, one of the Company’s senior officials in Banten.

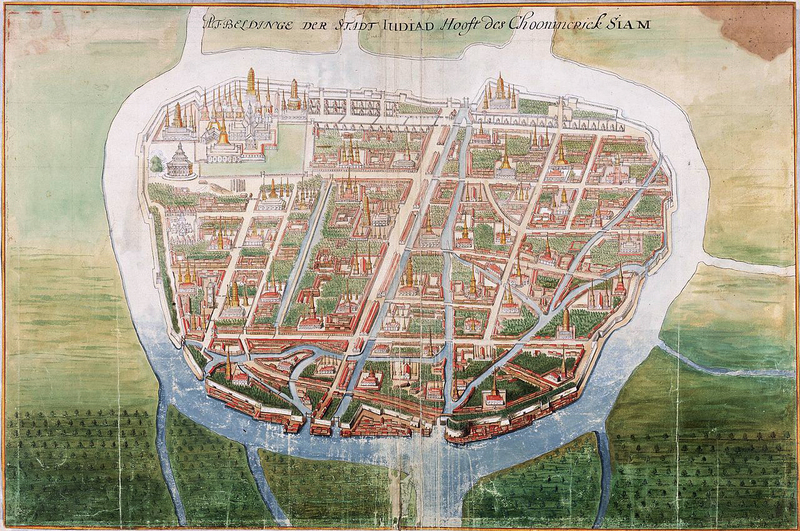

In 1678 Burnaby was sent to Ayutthaya, Siam’s capital city, to reorganize the Company’s chaotic finances. Ayutthaya in the 17th century was one of the largest and grandest cities in the world, where Portuguese, Dutch, English, Japanese, Vietnamese, Chinese, Mon, Persian, Indian, Makassarese and Malay merchants conducted a flourishing trade in this cosmopolitan metropolis. Burnaby, aware of Phaulkon’s talents and usefulness, contrived to take him along as a member of his staff.

View of Ayutthaya, 17th century

Burnaby persuaded George White, who was also in Ayutthaya at this time, to join the East India Company and to use his considerable knowledge of the Siamese trade to help him sort out the Company’s financial mess, a thankless and ultimately fruitless task. Phaulkon’s remarkable facility for language learning enabled him to master Thai in just a couple of years of living in Ayutthaya, working on various trading missions at the behest of Burnaby and White.

Private trade by Company employees was strictly forbidden, but impossible to enforce, and so, during one of the frequent attempts of the southern Malay-speaking provinces to gain independence from Ayutthaya, in this instance Songkhla, White and Burnaby decided to use the opportunity to send Phaulkon on a mission to secretly supply the rebels and make a handsome profit in the process.

Events contrived to cause the wheels of this business venture to fall off, disastrously so, and more to the point, dangerously so. Caught red-handed by the Thai authorities, the three men had to do some pretty fast talking to stall for time and avoid a potentially dire punishment. White and Burnaby came up with a plan to offer Phaulkon as an assistant to Phra Khlang, the Siamese minister responsible for regulating the trade with foreigners, in the hope that their recent misadventure in Songkhla would be forgiven, if not forgotten.

Not surprisingly Phaulkon was less enamoured of this plan than White and Burnaby, given that working for so powerful a man as the Phra Khlang, although tempting, was fraught with all manner of dangers, but in the end he took one for the team and agreed to do it. Once the Phra Khlang met Phaulkon and was suitably impressed by the young man’s linguistic talents and business acumen, and judged him to be worthy of the position, the die was cast.

The Phra Khlang

From that moment Phaulkon’s life took a dramatic turn, which launched him on a spectacular career that outstripped his wildest expectations and caused his friends and colleagues to marvel at his success and his enemies to froth at the mouth with impotent, jealous rage.

Put to work in the Treasury, Phaulkon’s ability and energy so impressed the Phra Khlang that he decided to introduce Phaulkon to the king, Narai, one of the most enlightened and Western-leaning monarchs of the period. Trusting his Phra Khlang’s judgement the king agreed and his faith quickly brought dividends.

Although most of the international trade of Ayutthaya was monopolized by the Dutch East India Company (the VOC), the local trade, the country or coastal trade as it was known, was firmly in the hands of Muslim traders of Persian and Indian origins, known at the time as ‘Moors’, many of whom also occupied positions of power throughout the kingdom.

One of the tasks they performed for king Narai was to provide the entertainment for visiting foreign embassies. Phaulkon took on this task and did so in far more splendid style and at far less expense, which not only caused these Moors great embarrassment but aroused their intense resentment at this upstart interloper’s intrusion into their cherished preserves.

Shortly afterwards, when these men presented the Treasury with a bill for their services to the king, Phaulkon was able to show that on the contrary they owed the king a vast amount, which after much bitter and rancorous argument and the incontrovertible logic of arithmetic, they were obliged to pay. When news of this reached king Narai’s ears he was delighted, and even more so when Paulkon came up with a plan to deal with one of the kingdom’s most serious threats.

A somewhat fanciful French portrait of king Narai

A constant worry for Narai was the unchallengeable power of the Dutch and their ability to threaten and bully his ministers into offering concessions and obtain monopolies over lucrative commodities. He had made overtures to the English East India Company to re-establish trade with Siam in return for their cooperation against the Dutch, but negotiations floundered on the excessive demands made by the EIC and their unwillingness to offer a firm commitment.

Phaulkon’s grand idea was to turn to the French, very recent arrivals in Asia and its trading network long dominated by the Dutch, Portuguese and English, but eager to make up for lost time. King Narai was enthusiastic and authorized Paulkon to initiate contact with the French and take the lead role in bringing the plan to fruition.

As a mark of his appreciation and growing respect for his ability the king conferred upon Phaulkon a title of nobility, making him a Luang Wijayendra, a ‘Lord of Victory’. With this title came control over the royal monopolies involving all commercial transactions with foreigners, making Phaulkon for the first time a man of real power and eminence.

French catholic missionaries had been active in Siam since the 1660s, tolerated and in many ways appreciated for the good works they performed for the community and it was through these contacts that Phaulkon worked tirelessly to bring about a closer relationship with France and Louis XIV, Europe’s most powerful monarch.

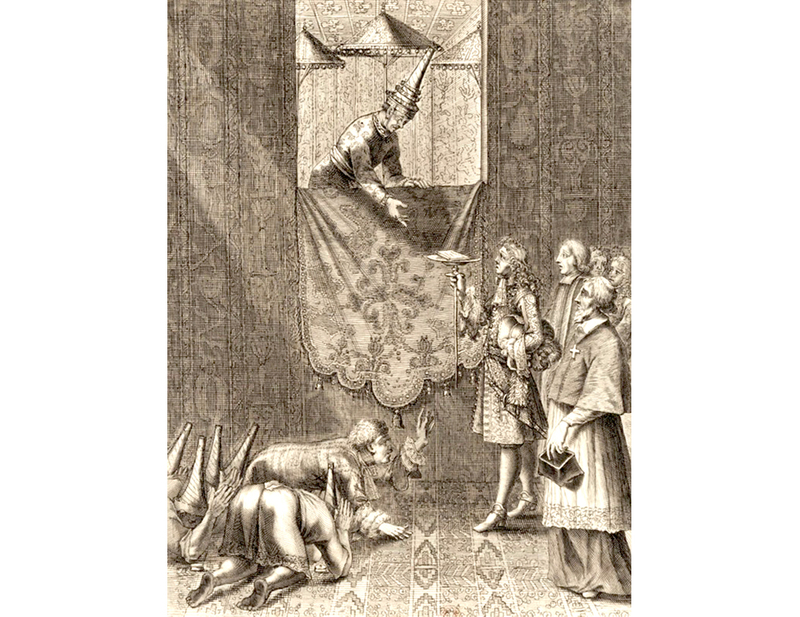

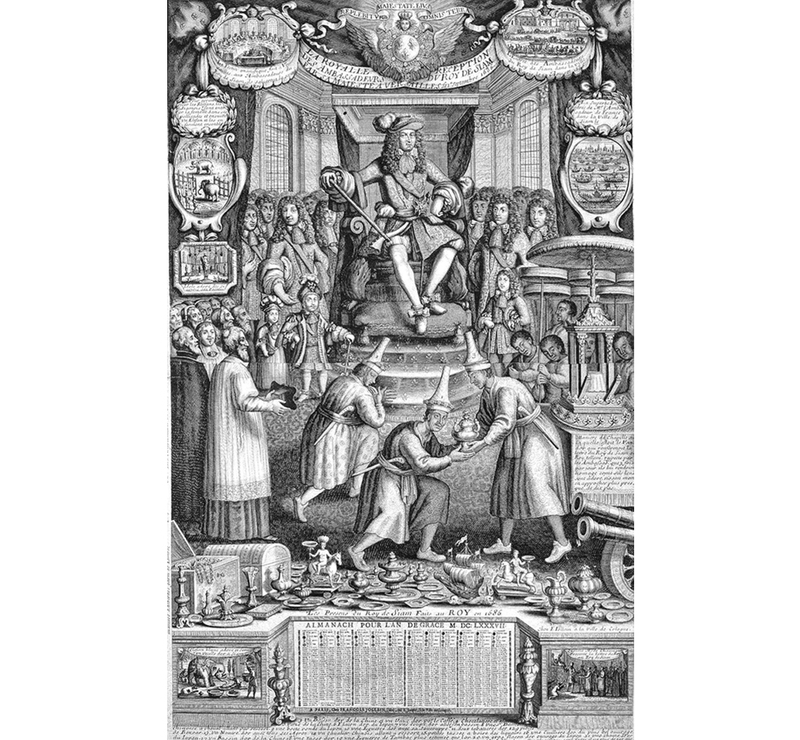

King Narai receiving French ambassadors

King Narai receiving French ambassadors

At first everything went swimmingly; lavish embassies and golden letters were exchanged and on every occasion Phaulkon was the conduit through which the king and the French representatives of Louis communicated. Phaulkon had made himself indispensable, not just for his linguistic skills, but also and perhaps more importantly for his astute understanding of the situation and the stakes that were on the table.

Louis XIV being presented with gifts by Siamese ambassadors

The French scientists, noblemen and senior clerical figures, who formed part of these embassies, were astonished at the size and impressed by the wealth of Ayutthaya, and once they’d met king Narai and were welcomed so warmly at sumptuously grand ceremonies and private audiences, ideas began to form in their minds that the king would be ripe for conversion to Christianity and that French influence over Siam could be achieved with little or no resistance.

Phaulkon did little to disabuse the French of their fanciful notions regarding Narai’s imminent conversion to Catholicism, though he knew full well that the chances of such a thing happening were non-existent. He needed to keep the French happy and to appease them for this inevitable failure he arranged for significant trade concessions to be granted and prepared the way for greater missionary activity within the kingdom with the king’s blessing.

With subsequent embassies the first French troops arrived, ostensibly to train Narai’s army, bolster Thai defences and offer a serious challenge to Dutch pretentions, but the ulterior motives of which soon became apparent to the more conservative Thai officials of the king’s court. They, together with the Muslim traders whose position of influence had been seriously eroded during Phaulkon’s tenure, began to show their resentment to policies that so blatantly favoured the French, allowed French troops to occupy strategic positions throughout the country, and increasingly favoured the king’s foreign favourite to the point where no one could be certain about who really wielded power in Siam.

An early example of cultural appropriation – the Comte de Forbin in the uniform of a Siamese admiral

The seething discontent felt by Siamese noblemen at what they believed was king Narai’s misplaced favouritism for foreigners and his increasing detachment from the Thai court led Narai to build a new royal retreat at Lopburi, safe from the political machinations and intrigue of his courtiers and ministers. Many of the buildings bear a strong European influence, indicative of Narai’s love for what he saw as progress and a reformation towards a more enlightened Siam. Phaulkon too built a palace, where his extravagant entertaining, which included an annual wine bill of staggering costs, astonished his foreign visitors.

Phaulkon’s palace, Lopburi

Phaulkon’s palace, Lopburi

By 1688, with French troops occupying forts and strategic points throughout the country and foreigners appointed to many of the leading governorships of provinces, Siamese resentment reached a point where drastic action seemed inevitable. One of Narai’s trusted advisers, Petracha, master of the Royal Elephant Corps, became the leader of a movement of conservative Siamese nobles bent on expelling all foreigners, eliminating Phaulkon’s influence and reclaiming its independence and returning Siam to its traditional ways.

The chance came in March of 1688 when Narai fell gravely ill and on May 17th to 18th the conspirators moved to take control. Phaulkon was arrested, and although he had been warned of the plots by Petracha and his supporters beforehand by a friendly Siamese courtier and could have saved himself and his family, he refused to the end to believe that he had done anything other than to act in the best interests of Siam.

Narai himself was put under house arrest, powerless to do anything to stop Petracha and his supporters from staging a dramatic series of events designed to reverse everything Narai and Phaulkon had worked for. French garrisons were attacked and ultimately all French forces were expelled from the country. On Narai’s death, possibly hastened by poisoning, Petracha declared himself king.

For Constantine Phaulkon the end was painful and brutal. On a brilliantly sunny day on the 5th of June, having endured weeks of torture, he was put on an elephant and taken into the forest near Tale Chupson where his sentence was pronounced. No eye-witness accounts of his tortures were recorded but his sunken cheeks, pale complexion and expression of pain and terror were evident to everyone who saw him.

Once the place of execution was reached he was ordered to dismount and told to prepare for death. He walked alone into a clearing to pray, after which he made a statement declaring his innocence and that all he had done was in the service of the king and for the welfare of Siam. He forgave his enemies and asked for his God’s forgiveness. He raised his eyes to the sky and extended his head forward. The executioner advanced towards Phaulkon and in the traditional manner with one blow cut of his head and with a second disembowelled him.

So ended the life and career of a remarkable man, who at the time was suspected by his enemies and detractors of coveting the throne of Siam for himself, but for a man as astute as Phaulkon this hardly seems a plausible claim. Phaulkon knew better than any of his European contemporaries how ludicrous a notion this was, given his experience of the Siamese court and its deeply xenophobic attitudes towards foreigners.

Phaulkon seemed to have had a genuinely deep regard for Narai, evident in his many efforts to find favour through his actions on Narai’s behalf, but there is little evidence to show that he planned to usurp Narai’s power. Narai in turn seemed to have regarded Phaulkon as the son he had always wanted, clever, resourceful and charming.

Perhaps it was the envy that this unusual relationship between a Greek adventurer and a Siamese king provoked that was the catalyst for his downfall, rather than the events that he and Narai brought about in their efforts to transform Siam.

From a distance of 330 years Constantine Phaulkon’s achievement seems all the more remarkable and is a fascinating story of a man with an eye to the main chance, who seized the astonishing opportunities offered him without hesitation, supremely confident in his ability to bend fate to his will. But, like a character from a Shakespearean drama, this pride and hubris ultimately proved instrumental in his fall from grace.

of collaborative energy

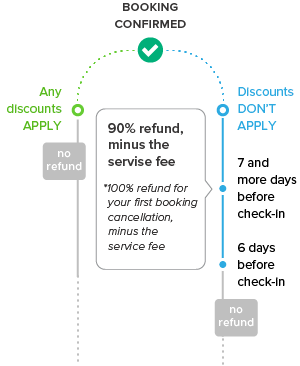

Before proceeding to use the website please carefully ready our Terms and Policies

I accept Diwerent's Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy