PHUKET ISLAND – MORE THAN JUST A PRETTY FACE

Human Settlement

With its long and vivid history of human settlement and cosmopolitan cultural influences it is somewhat fitting that Phuket today makes its living from tourism, welcoming millions of visitors from all over the globe. Conveniently placed along the trade routes between India and China, a safe haven from the monsoonal rains, it has always been subject to foreign influences.

The original inhabitants of the island were the so-called Negrito people, who were gradually displaced by later arrivals of Mon-Khmer and then Proto-Malays who migrated south from southern China, overland or by sea. Known variously as Orang Laut, Urak Lawoi, Chao Lay, Lawoi or Moken, and often called Sea Gypsies in English and Orang Laut (men of the sea) in Malay, they speak Austronesian languages closely related to Malay but strongly influenced by Mon-Khmer languages and Thai.

Related groups are found throughout the Southeast Asian archipelago and known by a multiplicity of names, but all share a similar lifestyle and seafaring culture. Though some of these groups continue to live as their ancestors did, in recent times the influence of the urban centres around which they live has proved ineluctable for the vast majority and in Phuket in particular absorption into the cosmopolitan mix is all but inevitable.

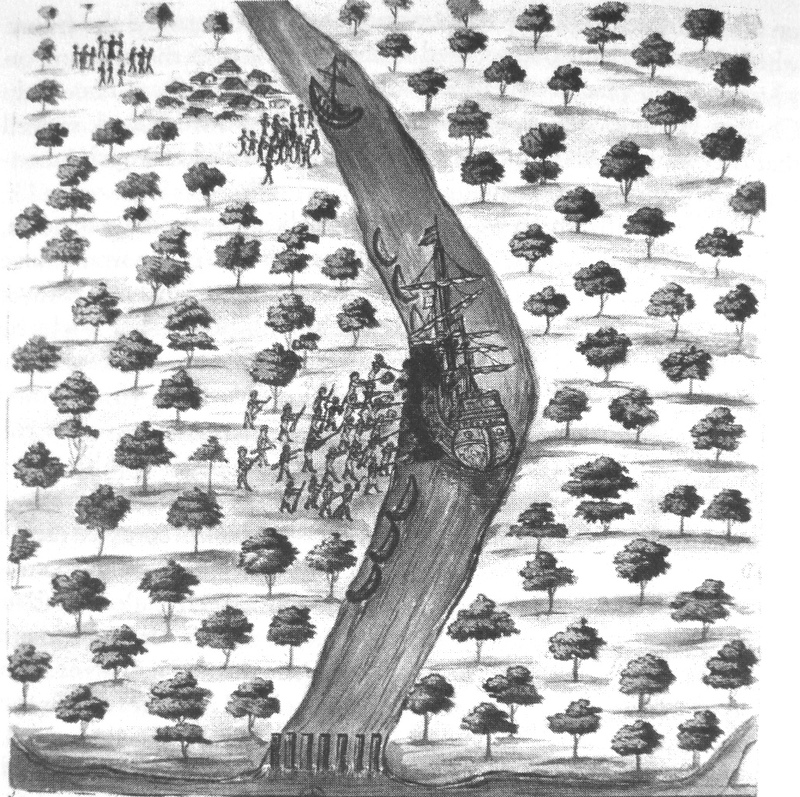

To the Portuguese they were known as Cellates, and Saleeters by the English, both derived from the Malay Orang Selat meaning ‘people of the straits, or the narrow seas’ and were regarded by all Europeans as notorious pirates up until the early nineteenth century when the growing British naval presence in the area gradually put an end to their depredations.

The seventeenth-century English captain and trader, Thomas Bowrey, wrote “The Saleeters are absolute Piratts, and are often cruising about Janselone (Junk Ceylon, Phuket) and Pullo Sambelon (Malay, Pulau Sembilan – The Nine Islands) &Isles near this Shore. They are subject to noe manner of Government, and have many cunning places to hide themselves and theire men of warre Prows (Malay, prau – boat) in Upon the Maine of the Malay Shore.”

A typical pirate craft, swift and predatory. Fearless and proud, pirates were the scourge of Phuket and surrounding lands for centuries.

Their numbers and the terror they inspired have since declined and they survive today by living on the fringes of more settled communities, spending almost the entire year on their boats apart from a few months on land during the monsoon.

The majority of the island’s population today are Thai and Buddhist, but about 20% are Muslim, primarily descendants of the original inhabitants and Malays who immigrated to the island over the centuries. People of Chinese ancestry are found in even greater numbers. The Peranakan, known locally as Phuket Baba, are the descendants of Chinese immigrants who arrived in Phuket between the 15th and 17th centuries, part of a greater movement of Chinese people throughout the Malay Archipelago - mainly Hokkien, Teochew and Haka speakers. Many others descend from the Chinese tin miners who arrived in the 19th century.

From Junk Ceylon to Phuket

Phuket was first incorporated into the Thai kingdom of Sukhothai in the thirteenth century when control was wrested from the powerful Srivijayan Empire of Sumatra. In the sixteenth century it was a valuable province of the Ayutthayan Kingdom and famous as a source of fine quality tin deposits, as well as being an important trading centre locally.

The name of the island is thought to be derived from the Malay word for ‘hill’, Bukit, suggestive of its appearance when viewed from a distance. The island was once called Thalang, again derived from the Old Malay word for ‘cape’, telong, and this is still the name used for the northern district, where the old capital was located. To Western travellers and navigators it was known as Junk Ceylon, a corruption of either Ujung Salang, which is Salang Point in Malay, or Tanjung Salang, Cape Salang.

Trade, Pirates and Naughty Dutchmen

Although visited by Indian traders as early as the first century AD, we get our first account of Phuket, and its much sought-after tin deposits, from Fernão Mendes Pinto, the famous Portuguese traveller, who arrived in Ayutthaya in 1545 and travelled extensively around the Siamese kingdom describing in detail many of its port cities with which the Portuguese, after their conquest of the Malay sultanate of Malacca (present-day Melaka), had been trading since the late 1520s.

Sometime in the late 1560s Portuguese traders had established a factory (not a place of manufacture in the modern sense, but rather a trading post) in Tha Rua, where today a popular and much frequented Chinese shrine is located, and later, in 1571, the number of Portuguese residents had grown large enough to warrant a wooden church being built by the Jesuits. In Cherngtalay, which nowadays is fast becoming a trendy new tourist hub, certain enterprising Portuguese established a flourishing tin mining operation of their own.

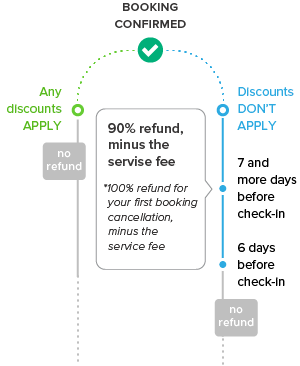

A 17th century Dutch trading post, or factory, typical of those established by Europeans in Asia.

Not all Portuguese though, were merchant adventurers or proselytizing missionaries. A rather sinister group of Portuguese pirates settled on a number of islands to the north of Phuket from where they attacked Muslim ships coming from India for plunder, and local craft in order to capture slaves for sale at a number of established slave markets in the region. So severe had their depredations become that the trade from Phuket’s ports went into a steep decline and despite a number of attempts by the Thai authorities to destroy this nest of freebooters the Portuguese pirates proved more than capable of defeating them.

Trade in Thailand was almost wholly conducted by foreigners, due primarily to the Thai and Malay disdain for an occupation they considered beneath them. The king’s representative in trade, the Phra Klang, would appoint Muslim Indians and Persians or Chinese as shahbandars, port officials, to supervise trade on the king’s behalf and act as governors, many of whom became powerful figures in Thai politics and were rewarded for their loyalty. One family in particular, the Bunnag, descendants of a certain Sheikh Ahmad and his brother, Muhamad Sa’id, who first settled in Thailand in 1602, remain politically and economically powerful today.

In the 17th century, Dutch merchants of the powerful VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), the Dutch East India Company, made their appearance in Thailand, and were particularly drawn to Phuket’s tin reserves with a view to gaining a monopoly over the trade. Tin was vital in the trade with China, being one of the few commodities offered by Western merchants that China would accept.

Signs of Western influence. A Farang (Westerner) stands guard at a Thai temple.

However, conditions on the island at the time of their arrival were not particularly conducive to trade, with Malay pirates, slave raiders, attacks from the Achinese of Sumatra and wars against the Burmese and Arakanese all contributing to a general level of lawlessness that brought most trade to a standstill, and this state of affairs lasted for most of the century.

On Phuket the Dutch built a fortified factory in Tha Rua in the early1640s but, despite their attempts to control and restrict trade, it did not prosper and Dutch business methods caused extreme resentment and alienated them from the local population. Inevitably, Dutch monopolistic practices over trade and their heavy-handed policy of backing up their claims with force – the VOC was by far the most potent naval power in Asia at the time - led to conflict with the Thais.

French Ambitions and Ruffled Feathers

In 1656, the year that King Narai ascended the throne, local inhabitants, infuriated by Dutch refusals to pay more for the tin ore they mined, despite an increase in its selling price, stormed the Dutch factory and killed a number of Dutchmen and later attacked the ship on which the survivors of the assault had taken refuge. The Dutch did not re-establish their factory on Phuket after this incident, having decided that it was too risky and unprofitable, although they sent ships periodically to trade for tin and kept a number of warships in the area to disrupt Phuket’s trade with India.

Violent confrontations between the Dutch and the inhabitants of Phuket escalated to such an extent that the Dutch decided to cut their losses and accept that the tin trade of Phuket was lost to them. Many English traders frequented Phuket during this time and several left accounts of their visits. One such merchant adventurer was Thomas Bowrey, mentioned above, who wrote A Geographical Account of Countries Round the Bay of Bengal, a highly informative and entertaining description of his travels in the 1670s and 1680s.

He was typical of the merchant adventurers of the time, operating independently of the big trading companies, the VOC and the British Honourable East India Company. King Narai welcomed the HEIC in the hope that they would act as a counter balance to Dutch influence, which at the time had become positively menacing, but their terms were excessive and ultimately unacceptable, and the private traders, like Bowrey, offered much better deals with no strings attached.

Having failed to interest the HEIC, Narai, through his Greek Phra Klang, the minister responsible for foreign trade, Constance Phaulkon, invited the French, who sent embassies, warships and troops to Thailand. All went swimmingly at first as Frenchmen began to assume positions of authority, notably in Phuket where several French commanders were appointed governors of Phuket and ports in Phang Nga, and, much to the chagrin of the Dutch, were given a monopoly over the tin trade.

Siamese ambassadors at the court of the ‘Sun King’, Louis XIV

Ultimately though, all this foreign influence and assumption of power by non-Thais was seen as a threat to Thailand’s sovereignty and independence by the more conservative princes and ministers of the court and of the largely Muslim trading community whose dominance over trade had been usurped. A palace revolution in 1688 brought about the fall and death of Constance Phaulkon, the expulsion of the French and the end of king Narai’s reign. The French attempt to conquer Thailand and convert its people to Catholicism had failed miserably and both Narai and Phaulkon paid the ultimate price for their follies.

Thai soldiers attack a French ship

Not surprisingly the Thais became somewhat less welcoming to foreigners from this point until the 19th century. Although Phuket became known as a lawless and dangerous place to visit, due to the rampant piracy prevalent in the region, some enterprising merchant captains, often referred to as country traders, did venture to the island in search of trade, especially for tin, the demand for which in China increased dramatically as did the price.

Trouble with the Neighbours

Although tin mining had its origins in the early 16th century it grew substantially in the 18th and 19th centuries, attracting large numbers of Chinese immigrants who worked the mines. Though conditions were extremely hard and despite the corruption of local officials and the exploitation of the Dutch traders they prospered. In time some of the more successful Chinese became governors of the island with the right to tax and exploit the local population and in so doing compete with the Muslim merchants who had hitherto been the dominant trading group on the island.

In the late 1781 a serious proposal to take control of Phuket submitted to the East India Company by British merchants resident on the island was approved and plans to take over the island and establish a private trading company initiated. Delayed due to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, it was once again sanctioned by the directors of the EIC only to be once again put on hold as a result of a large-scale Burmese attempt to conquer the island in 1785.

This invasion was thwarted by a heroic resistance of the ‘Heroine Sisters’ Lady Chan and Lady Mook, who despite being outnumbered used cunning and bluff to force the Burmese to withdraw. A statue to commemorate their achievement can be seen at the traffic roundabout on Thepkasattri Road in Thalang. Having secured Penang Island, the EIC decided not to pursue any future schemes to occupy Phuket and all plans were quietly shelved.

The Heroine Sisters monument, Thalang

From Tin Mines to Tourist Paradise

Throughout the 19th century Phuket prospered with new tin mines being established, notably at Kathu, and development proceeded apace. By the 20th century tin mining was conducted on an industrial scale and in the 1960s the Thai Sarco Company built the first tin melting plant and the high quality tin ore made large fortunes for a great many people.

In the 1970s the Tourism Authority of Thailand announced plans to develop Phuket into a major tourist destination and subsequently cancelled all mining concessions. The Kathu Mine Museum, opened in 2009, offers a very comprehensive and fascinating history of the tin mining industry that was once the lifeblood of the island and its influence on socio-economic, architectural and ethnic mix that makes the island quite unique.

The Sino-Portuguese shop houses and mansions, still much in evidence in Phuket Town, were built by the wealthy tin barons and offer an intriguing glimpse of what life was like on the island before the deluge of tourists transformed the economy and appearance of Phuket.

Phuket Town at night. Splendid Sino-Portuguese style shop houses

By the late 1960 thousands of US troops were in Thailand in support of the Vietnam War effort. A great many hotels, bars and restaurants catering to US servicemen on regular R&R breaks sprang up and Western influences in all aspects of life began to make an impact on Thailand’s traditionally conservative Buddhist outlook.

Phuket had an international airport by 1976 and during the 1980s and 1990s tourist numbers grew rapidly, attracted by the island’s stunning beaches and natural beauty, changing Phuket’s sleepy little fishing villages into a major resort, catering to visitors of every kind, from backpacker to jet-setter.

The 21st century has seen something of a boom in tourist numbers again after the financial crisis of 1997 and development of the island has grown enormously with support services industries to cater to demands of both visitors and permanent foreign residents. But, despite the face of modern tourism which is all most visitors ever see, there is much more to Phuket than meets the eye and for the curious the rewards are well worth the effort.

of collaborative energy

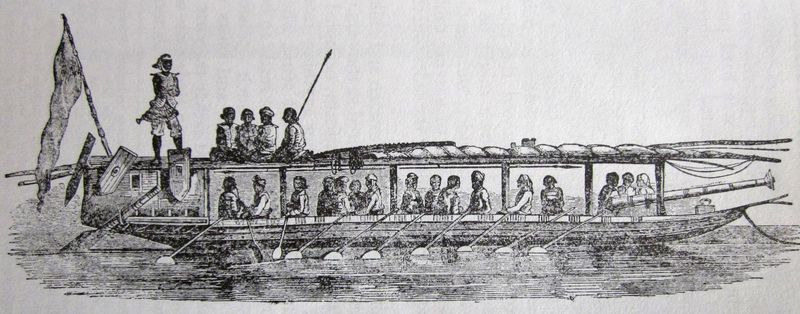

Before proceeding to use the website please carefully ready our Terms and Policies

I accept Diwerent's Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy