THE HEROINE SISTERS – PHUKET’S GALLANT SAVIOURS

In 1785, not long after the coronation of Thailand’s Rama I, King Bodawpaya of Burma launched a massive invasion. In what became known as the Nine Armies” War, nine Burmese armies were dispatched, seven to the north and west and two to the south of the country.

One of the southern armies crossed the Tenasserim Hills, the mountain range that separates the two countries, and was joined by rebellious Malay troops from Petani, Kelantan and Terengganu. Together these forces forced the Viceroy of Ligor to flee as a number of towns were taken.

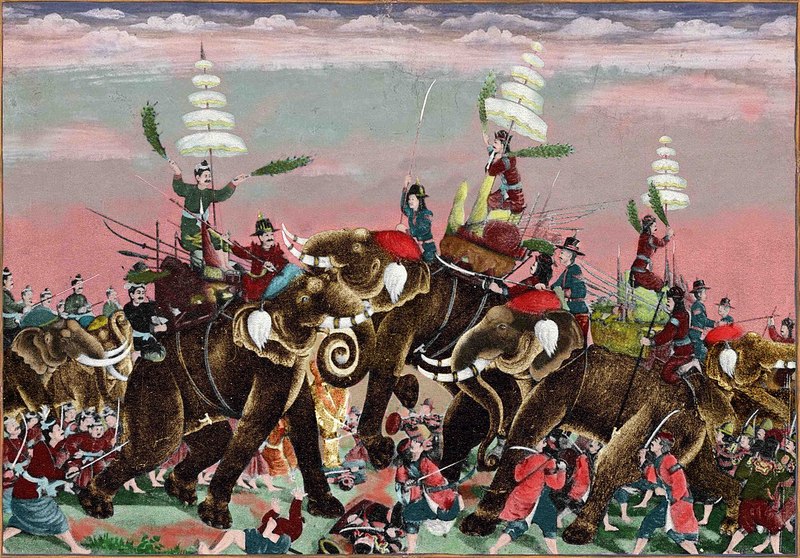

The elephant, the tank of Southeast Asian warfare.

The second southern army headed towards Phuket, aimed at stopping the supply of weapons from the island, brought in by foreign traders. The small forces available to the Thai commanders in Kok Kloi had very meagre forces at their disposal and therefore decided to face the Burmese invaders at the junction where the jungle trails the Burmese troops were marching along met at Kok Kloi.

Kok Kloi today has little to distinguish it from any other small, nondescript town in southern Thailand, apart from a long stretch of beautiful beach. It was here that the Burmese force of about 3,500 men landed before heading inland to attack the stockades hurriedly put up the Thais. Quickly overwhelmed by the Burmese troops the Thai forces fled, leaving the way clear for the Burmese to march on Phuket.

The situation in Phuket at this juncture was dire indeed. The governor, Phaya Pimon, had died about a month previously and no successor had yet been appointed. His widow, Lady Chan, at this time bout 45 years old, and her younger sister Lady Mook, were the islanders’ last hope.

Lady Chan was in Kok Kloi at the time of the Burmese attack for reasons which remain unclear and after the defeat she fled with the remnants of the Phuket militia to Thalang. Chaos reigned supreme everywhere. The islanders had heard of Ligor’s fall to the Burmese and there were rumours that Bangkok too had been taken. The prospect of Thai forces coming to their aid seemed slim to non-existent.

Lady Chan and Lady Mook knew that any attempt to escape by fleeing into the jungle around Phang Nga was probably futile as Burmese forces were already in the area looking for escapees to round up and sell as slaves. The decision was therefore made to defend Thalang Fort, built almost a century before by Rene Charbonneau, a French Jesuit missionary and engineer, and former governor of the island during King Narai’s reign.

Although well provided with cannon, muskets and gunpowder, the manpower available was somewhere in the region of 2,000 men, only a few hundred of which were trained soldiers, and these men were kept loyal largely by a regular supply of opium.

Everything edible was taken inside the fort and whatever couldn’t be carried away was destroyed to deny the enemy troops any resources. The islanders crowded into the fort and awaited the arrival of the Marauding Burmese, the main force of which had by this time landed on Nai Yang beach and advanced inland, looting and burning the towns and villages as they went. Another force arrived by boat along the klong, the canal, that led from Layan beach to Thalang.

As the Burmese forces ranged around the walls of the fort it soon became clear that they didn’t have sufficient artillery firepower to cause any substantial damage to the structure. They were outgunned and outranged by the much bigger and better British and Danish cannons of the fort. It was also reported at the time that Lady Chan, in order to convince the Burmese that the fort contained far more men than it did, had all the women, whose hairstyles at the time closely resembled those worn by Thai men, parade around the fort carrying sticks, made to look like muskets.

Although numbering about 3,000 in total, the Burmese were mostly lightly armed, some with muskets but the majority carrying only with spears and swords. They dug in and prepared for a long siege, which ultimately lasted 25 days and cost the Burmese around 300-400 casualties. Once their provisions ran out and their repeated attacks became less and less likely to succeed the Burmese commander decided to lift the siege and withdraw.

The ferocity of battle – brute force and hand-to-hand.

The ferocity of battle – brute force and hand-to-hand.

Though they showed indomitable spirit and resolve in resisting the enemy for as long as they did, the Burmese decision to raise the siege in the end might have had more to do with Rama I’s stunning victories over Burmese forces in the north and the rapid march south of another Thai army, which had defeated the Burmese and Malay rebels in Ligor, scattering the survivors, the Burmese back over the Tenasserim Hills and the Malays to their states in the north of the peninsula.

This series of defeats and setbacks rendered the Burmese position in Phuket as a base of resupply for the eastern forces redundant. Having denuded the island of food and looted everything of value, the Burmese took their captives and headed to their boats. The inhabitants of Phuket warily emerged from the fort to find their island utterly devastated.

The Burmese attack had been of little strategic value, but the damage to the economy, the destruction of crops, temples and houses, the hundreds of deaths and the enslaving of perhaps thousands of people all had a profound impact on the island’s economy and development for years. Phuket was virtually depleted of people and those that remained were destitute and faced the real prospect of starvation.

Tim mining operations ceased and as a consequence few if any foreign traders came with the necessary goods the island so depended on for survival. The newly appointed governor wrote to two frequent visitors to Phuket, the British traders Francis Light and James Scott to send desperately needed supplies of rice to stave off starvation.

The two sisters were rewarded by King Rama I for their splendid defence of the island with titles of honour, lady Chan becoming Thao Thepkrasatri and Lady Mook Thao Srisoonthorn. In 1967 the Heroines’ Monument was erected at the roundabout in Thalang. There is a small shrine at the base of the monument and many first-time visitors stop here to pay their respects before entering the town as a mark of homage to the achievements of these remarkable women.

A thriving night market in Thalang today.

A thriving night market in Thalang today.

Today the victory is remembered and rightly celebrated for its remarkable story of heroic resistance, but at the time the constant threat of another Burmese invasion and repeated slave raiding forays to Phuket kept the islanders forever anxious and many who had fled the island at the time of the Burmese attack never returned. There was precious little for anyone to celebrate other than survival, and a very precarious one at that.

of collaborative energy

Before proceeding to use the website please carefully ready our Terms and Policies

I accept Diwerent's Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy